Clifford Denton surveys the tragic abuse of Jews in Europe through the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages, by Church and State. What responsibility did Christians bear then - and what should our response be now?

In previous instalments our focus has been on the separation that occurred between Church and Synagogue, from the early centuries of the Common Era through to the 'Early Church Fathers'. Alongside this we have mentioned the parallel growth of anti-Semitism.

This, in turn, added further impetus to the separation, both as a fruit of, and as a contribution to, the gulf between the two communities.

This week we will look at the Middle Ages, where the fruit of anti-Semitism was coming to maturity.

Treatment of Jews by Christians

Marvin Wilson introduces this topic (Our Father Abraham, p98) as follows:

In the Middle Ages, Christian culture largely excluded Jews. Jews sought to avoid social, economic, and ecclesiastical pressures by living in secluded quarters of cities. They were considered useful primarily for one purpose, money-lending. This isolation from the larger society led Christians to accuse Jews of being a pariah people. Stripped of many personal liberties and victimized by an elitist "Christian" culture, Jews were required to wear a distinctive hat or patch sewn on their clothing. The very idea of "Hebraic" was commonly equated with "satanic".

Jews experienced a barrage of accusations. They were said to have had a peculiar smell, in contrast to the "odor of sanctity." Jews were also said to be sucklers of sows. They were held responsible for many evils, the "Christ-killer" charge still prominent. Jews were also called desecraters of the Host, allegedly entering churches secretly and piercing the holy wafer out of which "real blood" of Jesus flowed. They were accused of murdering Christian infants in order to use their blood (instead of wine) at the Passover Seder. During the Black Plague, which killed one-third of Europe's population, Jews were blamed for causing the plague by poisoning wells. [emphases added]

Such was the fruit of the early separation of Christianity from its Hebraic roots. We might have expected the world to persecute the scattered tribes of Israel. The Church should have mourned for them and comforted them, recognising their place in the Olive Tree of Romans 11.

The Middle Ages

And so we come to the Middle Ages, the years around 1000 AD. Theological differences between Christians and Jews had emerged even in the second century, strengthened by the philosophical ideas of the 'Church Fathers' that re-interpreted Scripture through the mindset of Plato and Aristotle. These things separated Christians from Jews so much that they would appear to have grown from the roots of two different trees. The next step was the persecution of Jews by 'Christians'.

By the Middle Ages, Christians and Jews had become so separated that they would appear to have grown from the roots of two different trees.

A prominent survey of anti-Semitism over 23 centuries is The Anguish of the Jews by Edward H Flannery (Paulist Press, 2004). We will consider some more of the details of anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages by reviewing chapters 4 to 6 of this book.

The Dark Ages

Flannery begins his survey by assessing the treatment of Jews in the Dark Ages, the centuries which preceded the Middle Ages (p66):

The Middle Ages meant one thing to the Christian, another to the Jew. For the latter, they not only began earlier and ended later but assumed a direction opposite to the general current of history. The earlier period, often called the Dark Ages, was for Jews a time of shifting fortunes but, as a whole, was relatively bearable. As the medieval period reached its culmination – the golden age of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries – the dark night of Judaism began.

The Dark Ages – from the fifth to the eleventh century – witnessed a world in travail...A great Empire in decline, ceaseless barbarian invasions, Persian wars and Moslem encirclement – such were the elements of disarray from which the Church, sole unifying force extant, was to forge the unity that would be Christian Europe...It was a period in which the mantle of temporal as well as spiritual governance was often thrust upon the Church, but one, conversely, in which its spiritual authority often suffered encroachment.

Judaism's situation presented a picture as chaotic as that of the times. Little can be said that applies to all Jewry or to the whole period. Hence the necessity of following the vagaries of Jewish fortunes from East to West, from Gaul to Spain, Persia to Arabia where their prosperity or degradation depended as much on the will of pope, king, bishop, council, caliph, noble, or mob as it did on law. Recalcitrant to the emerging unification, Jews received special attention almost everywhere. Jewish-Gentile altercations were not the infrequent result, but by and large, on the popular and often ecclesiastical and political level, Jews fared well. [emphases added]

Conflicts and Restricted Rights

Roman law imposed itself on the Jewish world as on other people groups. In the Eastern Empire Jews were often resentful of restrictive measures. In addition to this, at times Christians ignored statutes that protected Jewish rights. This led to conflicts, including those at Antioch. There were massacres and burnings of synagogues in the reign of Zeno (474-91). This continued into the following century, one recorded incident being when, "a monk of Amida, named Sergius, incited a mob and burned down a synagogue, in the wake of which a veritable contest of church and synagogue burning and rebuilding ensued" (quoted by Flannery, p68).

The Emperor Justinian (483-565) enforced new legislation which was far more restrictive on Jews than before. Among the restrictions was a narrowing of property rights, a barring from public functions and the inability to testify against a Christian. Jews could not celebrate Passover before Christian Easter. The Bible could not be read in Hebrew, and the Mishnah was banned. Those who did not believe in the resurrection, the last judgment or the existence of angels were to be excommunicated and put to death.

These were among the measures intended to bring Judaism under some sort of control, but it instead brought exasperation and later in the century resulted in violence, including the killing of many Christians in Antioch at the turn of the century. Many Jews joined the Persians in 614 in the conquering of Jerusalem where 30,000 Christians were killed.

In the fifth and sixth centuries, measures introduced to bring Judaism under control instead brought exasperation and outbreaks of violence.

There was retaliatory action from Christians later and many Jews were killed when Jerusalem was retaken under Heraclius in 628. Once more Jews were barred from the city. Heraclius, like some others, attempted to bring unity by forced baptisms of Jews.

Judaism a Crime

Judaism became a sort of crime against the state for several centuries. The Second Council of Nicaea (787) prohibited Jews who practised Judaism in secret to be admitted to the Church or sacraments. It also insisted on their practising aspects of Judaism openly once they were baptised but, as Flannery points out:

The Church's prohibition, reiterated many times during the next millennium, seemed powerless against the medieval urge to enforce religious and cultural unity. The history of forced conversion would be long, heartrending, and bloodstained before it reached its high point centuries later in the Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella. (p71)

Though there was more acceptance of Judaism in the Western Empire at this time, the same tensions caused by the exaltation of Christianity over Judaism still existed. In the reign of Pope Gregory I (590-604), there was a zeal to convert Jews and to suppress Judaizing. However, Jews were given legal right to attend their synagogues.

Forced Conversions

Persecution did break out in Spain in the reign of King Sisebut (612-21). The Jews were given the ultimatum to be baptised or go into exile. Approximately 90,000 were converted while many thousands fled the country.

Later it was observed that forced conversions were not really effective and tensions remained. Baptised children of un-baptised Jewish parents were taken from them for a Christian education, a practice that occurred in later centuries too. We read that later:

The summit of oppression was reached under King Erwig (680-87), who enacted twenty-eight laws designed to make the existence of Jews and Judaizers intolerable: Jews were ordered to accept baptism; Jewish converts must obtain a permit from a priest to undertake a journey; they were forced to listen to Christian sermons and forbidden to make distinctions among meats; evasions and bribes by Jews and lax enforcement by authorities were prohibited; and, finally, blasphemies against the Christian faith were made punishable. The twelfth council of Toledo (681) confirmed these measures.

Toward the end of the century, with Islam menacing his kingdom from North Africa where many Jews had fled, King Egica (d. 702), after first attempting to soften their lot, decreed conjointly with the sixteenth council (693) that the Jews must abandon commerce and surrender all property acquired from Christians. The seventeenth council (694), again in conjunction with the king, accused the Jews of conspiracy with their king in North Africa, reduced them to perpetual slavery, banned all Jewish rites, and ordered all Jewish children above the age of seven to be taken and reared as Christians. (Flannery, p77)

During the seventh century persecution broke out in Spain, with forced conversions, exile, enslavement and the confiscation of Jewish children.

The Visigoth Kingdom

The Muslims conquered Spain by 711 and the lot of Jews improved – indeed, a new 'golden era' began where Jewish scholarship was allowed to take on new life. The Visigoth kingdom, which had covered much of south-western Europe for the 5th–8th centuries, was removed. It is considered that the maltreatment of Jews in the Visigoth kingdom of Spain had been a direct result of the union of Church and State, however, the effect of this union was not uniform. For example, Jews fared much better in France in the same period that they were persecuted heavily in Spain.

Nevertheless, wherever there were Jews in the Christianised world there was constant debate in the church councils and resulting tensions to one degree or another, as well as some restrictions associated, for example, with the Feasts and dietary laws.

Wherever there were Jews in the Christianised world there was constant debate in the church councils and, as a result, tensions to one degree or another.

What Kind of Anti-Semitism?

As a general comment on the phase of anti-Semitism up to the turn of the first Millennium, we see it as having greater intensity in the East than in the West and, in the West, greater in pre-Muslim Spain than in France. Flannery writes about the character of this anti-Semitism:

...there was in this era no popular or economic anti-Semitism. Yet there was a juridical or legislative anti-Judaism. Jews were not opposed as persons or as a people, and indeed heretics still fared worse than they. The Church still had reason to worry about Jewish influence in social and religious life. The Talmudic withdrawal of Judaism was never complete. Many Jews, especially those who reached posts of influence in civic or economic spheres kept the doors to and from the Christian world open.

The legislation of church and state must, in effect, be seen, above all, as a defense against Jewish proselytism. The perennial laws against employment of Christian slaves, holding government office, and Jewish-Christian intimacies were motivated by religious scruples rather than political or social considerations. (pp88-89)

Flannery writes that this period was characterised less by anti-Semitism and bad feeling against the Jews themselves, than by a legal anti-Judaism enforced by both church and state.

After 1000 AD

The intensity of anti-Semitism increased after the year 1000 and grew to terrifying proportions. Flannery writes (p90-91):

During the first half of the second Christian millennium, the history of anti-Semitism and the history of Judaism so converged as almost to coincide. It is a scandal of Christian history that, while the Church and the Christian State were at the zenith of their power and influence, the sons of Israel reached the nadir of their unending oppression. This was the age of Innocent III and Henry II, Gregory VII and Henry VI, of the Crusades, of Aquinas and Dante, of St. Francis, of Notre Dame and Rheims Cathedral; but it was no less the age of anti-Jewish hecatombs, expulsions, calumnious myths, autos-da-fe, of the badge, the ghetto, and many other hardships visited upon the Jews...

The year 1000 found Jews in conditions reasonably stable for the time. Two centuries later they were almost pariahs; in three, they were terrorized. What occurred in this span to effect such a change? Some observers speak of the Church's "teaching of contempt" finally taking hold and suddenly seeping down to the populace. True, but the matter appears more complex. The eleventh century – as a period of incubation – contained certain events that foreshadowed the future. When Hakim destroyed the Holy Sepulchre in 1009, the Jews of Orleans were accused of collusion – an improbable charge since Jews as well as Christians were persecuted by that mad caliph. Nonetheless, widespread persecution of Jews resulted.

Again in 1012, when Jews were expelled from Mainz by Henry II, the expulsion was a repercussion of the earlier charge of treason, and doubtless also a reaction to the conversion to Judaism of Wecelinus, chaplain of Duke Conrad in 1006. In the "Crusade of Spain" against the Saracens in 1063, the Jews were disqualified for armed service and were attacked by the soldiers on the march. In short, renewed suspicions of Jewish complicity with Islam heightened the sense of the Jews' alien and infidel character, thus readying the atmosphere for the storm about to break over Judaism at the close of the eleventh century. [emphases added]

From this brief overview of the first part of the second millennium we perceive that widespread and multi-faceted persecution of Jews grew across the nations that had been 'Christianised' through Roman influence at the time of Constantine. To explore this fully is a task beyond the scope of this series. However, it is essential for students of Scripture to be informed about this era, so we will illustrate the extent of this persecution through some of the key events.

The Crusades

It is considered that the First Crusade of 1096 was a tragedy for the Jewish world measurable against the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD and the Holocaust of the Second World War under Hitler. In Flannery's words:

Great, illorganised hordes of nobles, knights, monks, and peasants – "God wills it" on their lips as they set off to free the Holy Land from the Muslim infidel – suddenly turned on the Jews.

Along the route to the Holy Land taken by the crusaders, Jews were offered the choice of baptism or death. Massacres took place in Rouen, along the Rhine and Danube, at Worms and at Mainz, in Treves, Neuss, Ratisbon, in Bohemia and in Prague. Some Jews preferred suicide to baptism. From January to July of 1096 it is estimated that up to 10,000 died, probably one third of the Jewish population of Germany and Northern France at the time.

The Jewish world was stunned and the rift between Judaism and Christianity was magnified. Christians were viewed by some as capricious assassins, ever ready to strike. But out of the suffering, a new heroism was born. A cult and tradition of martyrdom was instituted whereby Jews who gave their lives "to sanctify the Name" (Kiddush ha Shem) were greatly revered; their remembrance became part of the synagogue service. (pp91-3)

The Second Crusade of 1146, while not so intense as the first, brought further outbreaks of violence against the Jews. This time there were moderating influences from some Christian leaders, including Emperor Conrad II, King Louis VII of France and Bernard of Clairvaux. Another issue entered in, however, to divide Christians from Jews and contribute in some places in Europe to the violence associated with this Crusade:

Since the First Crusade, Christians had become more active in commercial affairs and so now resented their Jewish competitors. Moreover, Jews were more deeply involved in money-lending, a practice which drew upon them the hostility of both the clergy and the people. Pope Eugenius III (1145-53), who called up the new Crusade, suggested to the princes, as an inducement to enlistment, crusaders be absolved of their debts to Jews. (p94, emphasis added)

Peter of Cluny exhorted Louis VII that Jews, "like Cain, the fratricide, they should be made to suffer fearful torments and prepared for greater ignominy, for an existence worse than death" (quoted in Flannery, p95).

The First Crusade of 1096 was a tragedy for the Jews that has been since likened to the Holocaust of WW2. 10,000 were massacred or committed suicide in the space of six months.

Bought and Sold

A result of a certain amount of protection that Jews sought and acquired from Emperors Henry IV and Conrad III during the period of the Crusades led them to being considered as 'Servants of the Royal Chamber'. Their freedom was curtailed through legislation at various times: "The attachment to the imperial chamber reduced Jews to the status of pieces of property that could be – and were – bought, loaned, and sold as any other merchandise. Kings paid off barons and barons paid off creditors with Jews" (quoted in Flannery, p95).

In addition, the message of Paul in his letters (Rom 9:13, Gal 4:22-31, wrongly applied) was used to imply that Jews were inferior to Christians. This perpetuated, from a theological standpoint, the servitude of the Jews and their barring from public office.

Forced out of many areas of social and commercial life, by the 12th and 13th centuries money-lending became the means by which many Jews survived: "At every turn, he was faced with special taxes, confiscations, cancellations of credit, expulsions, and threats of death. He had literally to buy not only his rights but his very existence. Money became to him as precious as the air he breathed, the bread he ate." (p97) The caricature that later became Shakespeare's Shylock began in these days of Jewish survival.

Forced out of many areas of social and commercial life, by the 12th and 13th centuries money-lending became the means by which many Jews survived – and so developed the caricature.

Myths and Rumours

Another significant attack on Jews came from the so-called 'ritual murder' or 'blood' libel. This occurred in a number of places. The first incident was in Norwich, England in 1141 where the body of a dead boy was discovered on Good Friday. Jews were believed to be the culprits following a story that they planned to carry out a murder once a year in derision of the death of Christ.

This same accusation occurred in other towns of England and on the Continent where additions were often made to the story, such the drawing of blood for magical purposes by Jews and the taking of Passover communion with the heart of a murdered child.

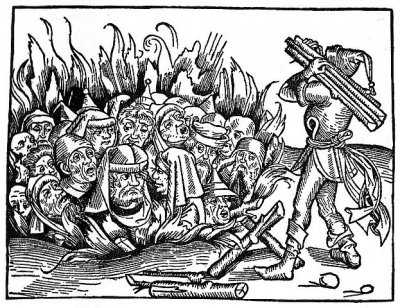

Hundreds of incidences of this kind occurred and many Jews were slaughtered following rigged trials. In 1171 in Blois, 40 Jews were burned, for example. Excused by this blood libel, King Philip Augustus, on a single day in 1182, had all Jews arrested, freed for a ransom and expelled from his realm, only to recall them sixteen years later, and appoint them as money lenders to be taxed heavily. All this was for the purpose of acquiring money from the Jews.

Cheating and Humiliation

At the time of the Third Crusade of 1189 his persecution continued with the canceling of all debts to Jews. These are examples of the trend that continued in relation to the financial persecution of the Jews, including those enacted by the Popes, such as the measures adopted by Innocent III in the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215.

Out of this Church Council also came the tradition of a Jew having to wear a distinctive badge of identification. The justification was to help curtail intermarriage between Christians and non-Christians. Later, in France, the badge was a yellow sphere, and in Poland a pointed hat, with different symbols elsewhere.

In the 13th century, Jews were made to suffer financially and were also forced to wear humiliating badges of identification.

A further result of the hate of Jews began in 1240 following an accusation to Gregory IX by a Dominican by the name of Nicholas Donin. He produced 35 theses to propose that the Talmud was the chief cause of Jewish unbelief and an offence to Christians. The Talmud was put on trial and eventually the case against it, which was quite complex, assumed proven and 24 cartloads of the Talmud were burned in Paris.

The Black Death

These brief examples serve to illustrate the immensity and the multifaceted nature of unrelenting aggression that was leveled against the Jews in these centuries. We finish the survey with one more example. In Europe, between 1347 and 1350 an epidemic called the Black Death killed one third of the population. The Jews were blamed – and then attacked:

For Jews it was a tragedy to which, after the fall of Jerusalem, only the horrors of 1096 and 1939 were comparable. For three hellish years (1348-50) Jewish communities all over Europe were torn to pieces by a populace crazed by the plague which, before it ended, carried off one third the population. Bewildered by the plague's ravages people looked for a cause. Before long the inevitable scapegoat was found. Who else but the archconspirator and poisoner, the Jew?

This time, too, the weird formula for the well poisonings – elicited by torture – was disclosed: a concoction of lizards, spiders, frogs, human hearts, and, to be sure, sacred hosts. The story that Jews in Spain had circulated the death-killing drug to poison the wells of all Christendom spread like wildfire. It was first believed in Southern France, where the entire Jewish population of a town was burned.

From there the deathly trail led into Northern Spain, then to Switzerland, into Bavaria, up the Rhine, into East Germany, and to Belgium, Poland, and Austria...In all, over 200 Jewish communities, large or small, were destroyed...the massacres were greatest in Germany where every sizeable city was affected...Well over 10,000 were killed in Erfurt, Mainz, and Breslau alone. [emphasis added. Flannery, p109]

Summary

Here we have an indication of the depths reached as a result of the division between Church and Synagogue which began in relatively small ways in the second and third centuries. Theological division was perhaps the major root cause (along with theological misinterpretation) of the divergence of the two religions, led by the dominant Christian majority when Christianity became politicised.

The catalogue of disasters is immense and what we have described can be added to with many other examples, such as the conquering Crusaders herding the Jews of Jerusalem into their synagogue and singing hymns while they burned them to death "in the name of Jesus"; or the Spanish Inquisitor Torquemada holding the Spanish Jews in a state of terror in the late 1400s, resulting finally in their expulsion from Spain on 30 July 1492, through the edict by Ferdinand and Isabella.

Then on and on, from peak to trough through the Holocaust and Pogroms, to the present day. Here in the depth of anti-Semitism we see the consequences of the separation of the Christian Church from its Hebraic foundations.

For Reflection and Comment

- How can Christians respond to this terrible history of anti-Semitic violence and persecution?

- What can Christians do to ensure that anti-Semitism is no longer evident in the Church?

Next time: Emergence of anti-Jewish Christian Theologies.